The Hidden Nerve That Could Rewrite Everything We Believe About Hamstring, ACL, and Achilles Injuries

After dropping my piece on high-velocity eccentrics and peripheral nerve damage, I went down a rabbit hole — the sciatic nerve. The big one. The heavyweight. The electrical pipeline controlling most of what matters in sprinting, cutting, stabilizing, and not blowing out a hamstring mid-stride.

And I asked myself:

If the sciatic nerve hiccups, even for a moment… does the entire lower-body injury conversation fall apart?

Turns out, the answer is bigger than “maybe.”

It’s closer to: “Holy hell, we’ve been missing something massive.”

The Discovery That Stopped Me Cold

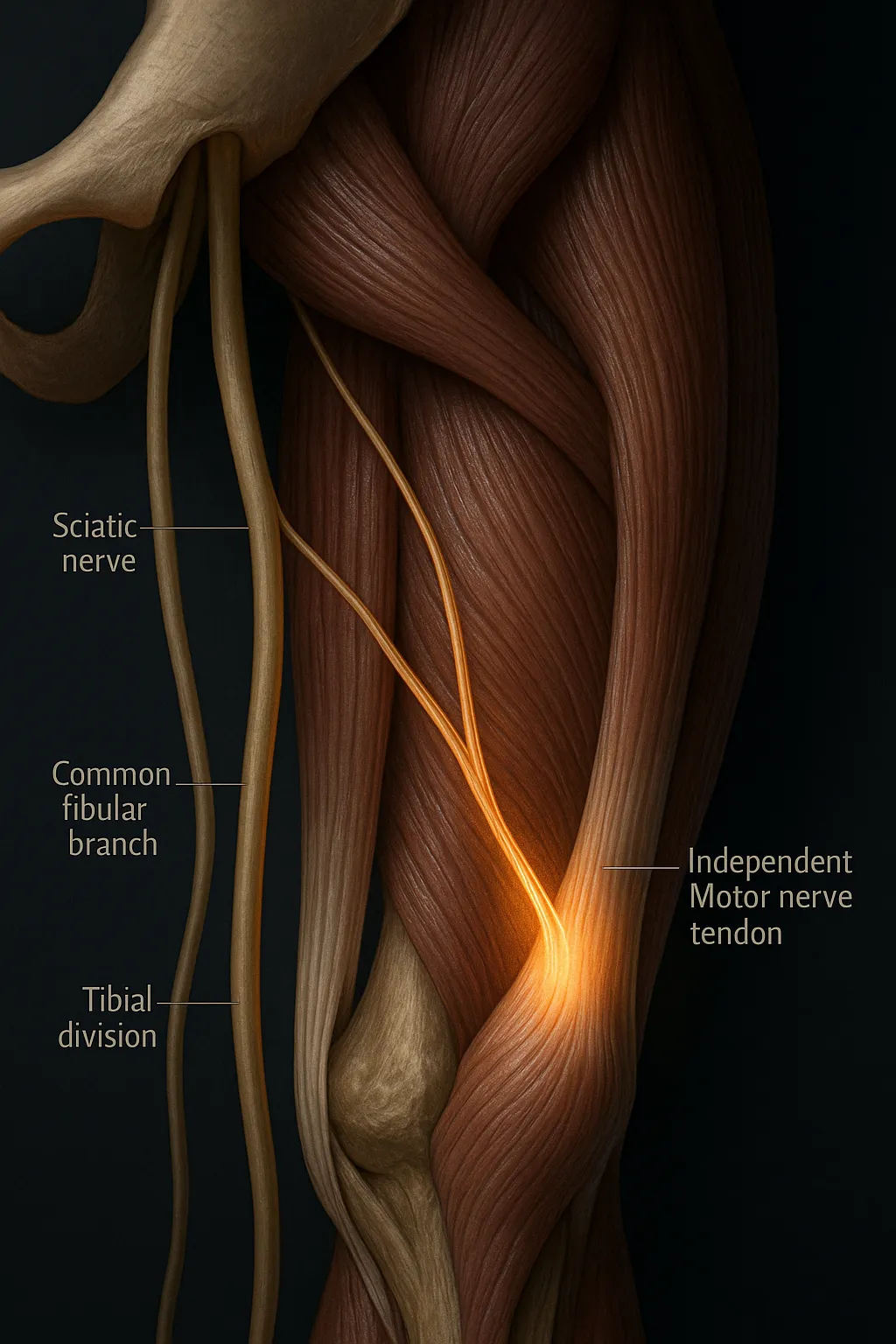

While tracing the sciatic nerve’s branching patterns, I ran into a 2024 study by Kozioł et al. — and this single detail detonated everything I thought I understood:

👉 The proximal hamstring tendon has its own independent motor nerve branch.

Not the muscle.

Not a shared signal.

The tendon itself receives its own motor command.

And this wasn’t a rare find. It was present in 100% of specimens.

65%: tendon had a dedicated branch all to itself

~20%: branch split supply between tendon + biceps femoris

Remaining cases: tendon got its signal from another trunk

No matter the routing, the takeaway is the same:

The tendon is not just a passive cable. It is a neuromechanical structure with its own motor drive.

Let that sink in.

Because this isn’t in any coaching certification.

It’s not in injury-prevention models.

It’s not in biomechanics textbooks.

It’s not in sports-performance literature.

As far as I can tell, nobody in the performance world is talking about this — which is wild considering how often this tendon blows up in elite sport.

So I’m naming it:

Neurotendinous Function

The idea that a tendon possesses independent motor innervation — and therefore may act as its own neuromechanical driver.

Cool name. But now comes the uncomfortable truth…

We Have No Idea How This Tendon Nerve Actually Behaves

Zero published research on:

when the tendon’s motor branch fires

whether it activates before or after the muscle

how it modulates stiffness

how it reacts under fatigue

whether it can fail even when the muscle is fine

whether neural delay creates the perfect storm for non-contact injuries

Think about it:

If the tendon and muscle receive different signals, then everything we assume about “muscle–tendon unity” might be wrong.

They might not fire together.

They might not fatigue together.

They might not protect each other under load.

They might fail for completely different reasons.

This isn’t a tweak.

This is a tectonic shift.

The Questions No One Has Asked — Until Now

If the tendon has its own motor supply…

Could a misfire be the hidden trigger behind those brutal terminal-swing hamstring tears?

Could proximal tendinopathy be partly neural, not just mechanical?

Could delayed tendon activation be the ghost in the machine behind ACL injuries during deceleration?

Could conduction issues in the tibial or common fibular branches be the silent assassin in Achilles ruptures?

Does tendon neural fatigue happen earlier — long before an athlete “feels” fatigued?

We don’t know.

Because nobody has studied it.

And that’s exactly the problem.

Where We Go From Here

If Neurotendinous Function is real — and the anatomy says it is — then the entire injury-prevention model must evolve:

Strength testing alone can’t predict tendon risk.

Eccentric loading can't protect a tendon whose nerve is the real bottleneck.

High-speed mechanics must include tendon-specific neural timing.

Rehab may need to target neuromotor pathways no one has considered.

Sports science needs to move — fast — because this is the kind of blind spot that creates preventable injuries.

We need to study:

tendon-branch firing patterns during sprinting

tendon-specific neural fatigue

conduction delays as precursors to catastrophic failure

whether training can strengthen or optimize tendon-nerve pathways

This is a new frontier — the kind that doesn’t come around often.

And yes… I could be wrong. I’m open to it.

But with the hamstring tendon’s injury rate, ignoring this would be reckless.

If you’re researching this quietly, or running unpublished data, reach out. This conversation needs every sharp mind available.

At Possibility Institute, we help the world’s most powerful athletes — and everyday performers — win more, hurt less, and age like they mean it.

#SportsPerformance

#NeuroTendinousFunction

#InjuryReductionBreakthrough

#TapInForTheFuture

#HumanMovementScience